Webinar: Scaling up NbS for adaptation in coastal areas

Background

Coastal environments form the interface between the land and sea or ocean. They host key infrastructures, ecosystems and about 40% of the world’s global population. In 2018, a study of the economic robustness of protection against 21st-century sea-level rise concluded that it is economically beneficial to protect 13% of the global coastline, a proportion which encompasses 90% of the global floodplain population.

One of the most certain consequences of global warming is an increase in global sea levels. More intense and frequent extreme sea-level events, together with trends in coastal development are expected to increase expected annual flood damages by two to three orders of magnitude by 2100.

Solutions for adaptation in coastal areas

To safeguard the livelihoods of the 100 million persons who live within one meter of the mean sea level and the existence of some islands and deltaic coasts, adaptation needs to be accelerated. Adapting to sea-level rise typically entails large-scale investments in grey infrastructure with a long lead time for planning and implementation. Hard coastal protection measures are widespread and provide predictable levels of safety. These have potentially large societal impacts on current and future generations.

In contrast, nature-based solutions (NbS) are not yet widespread. These are environmentally friendly designs that can work with grey infrastructure or be independently designed and implemented.

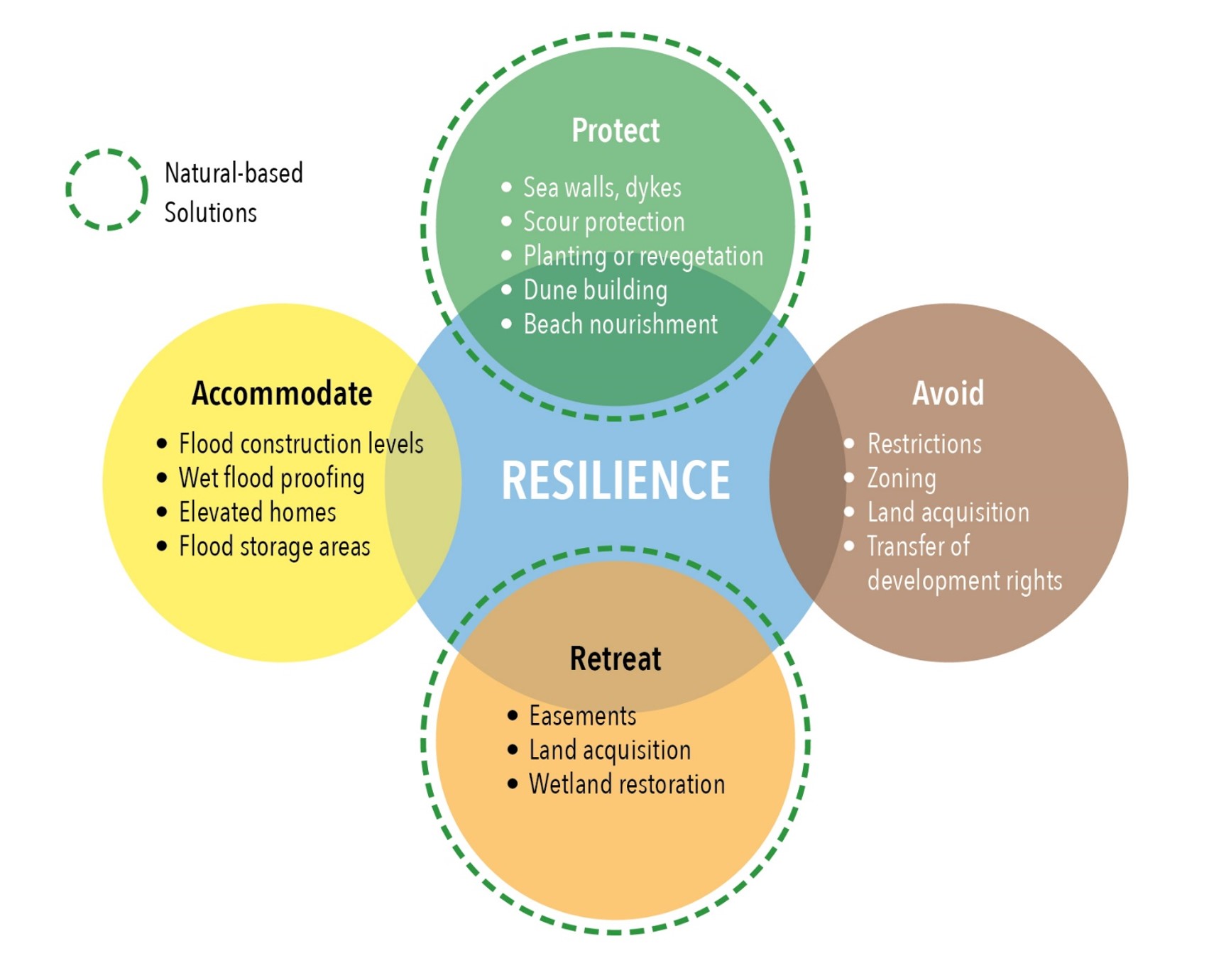

In the face of deep uncertainty there is a need to support decision-making by choosing an appropriate and accepted strategy that comprises one or more of the following: protect/defend, accommodate, advance, and retreat. However, there are challenges in implementing these solutions and a need for upscaling of good examples and sharing of lessons learnt. Financing, community engagement, policies and expertise are some of the constraints.

Purpose of the webinar

GCA’s Water Adaptation Community organized a webinar on the 23rd of June on coastal adaptation using NbS. Speakers presented different coastal adaptation strategies and examples of how NbS have been included used for coastal adaptation, and challenges and opportunities for upscaling.

This event convened local private sector partners and stakeholders and was organized by the knowledge and innovations broker of the Akkoord van Groningen, a strategic partnership between the university, vocational training schools, the municipality and the province aiming to develop the city and province into a prime knowledge and innovation hub on global issues.[1] GCA is a partner of the Akkoord on climate change adaptation.

Speakers

- Joanna Eyquem (facilitator), Managing Director of Climate-Resilient Infrastructure at the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation, University of Waterloo, Canada.

- Albert Vos, Project manager, for the intergovernmental project IBP VLOED in Eems-Dollard

- Ole Fryd, associate professor in landscape architecture and planning at the university of Copenhagen, bringing some examples from Denmark.

- Capitaine Didier Kabo, Conservateur de l'Aire Marine Protégée de Saint-Louis au Senegal. Aussi au Senegal

- Moussa Sall Coordinateur de l’Observatoire Régional du Littoral Ouest Africain (ORLOA) à Dakar

- Paul Sayers, founder and director of Sayers and Partners, UK.

- Floris Boogard, a Senior Consultant at Deltares as well lecturing Hanze University of Applied Sciences, Groningen

- Lin Fen-Yu (Vicky Lin), project manager at Blue 21, The Netherlands

Summary

NbS and coastal protection

Nature-based solutions to coastal adaptation consider flooding and erosion in tandem with people and nature, the speakers said. The conventional approach to coastal flooding and erosion has been to view them as technical problems to be solved by building grey infrastructure.

NbS has only recently entered the lexicon but is as yet underused and undervalued. They are harder to implement and take longer to fructify than grey infrastructure, said Joanna Eyquem. However, there is an international trend toward strategic solutions and long-term, work with natural processes, combining structural and non-structural measures and working with grey infrastructure.

There are four broad approaches to coastal adaptation:

Protect, which reduces flood risks by building infrastructures such as sea walls and dykes. Increasingly, NbS such as planting or regeneration of coasts, dune building and beach nourishment are being used.

Accommodate, which is largely about building above flood levels, wet flood-proofing by elevating homes and construction of flood storage areas.

Retreat involves acquiring flood-prone land, wetland restoration and easements.

Avoid which activities are restricted in certain places, zoning, land acquisition and the transfer of development rights.

A fifth is non-intervention.

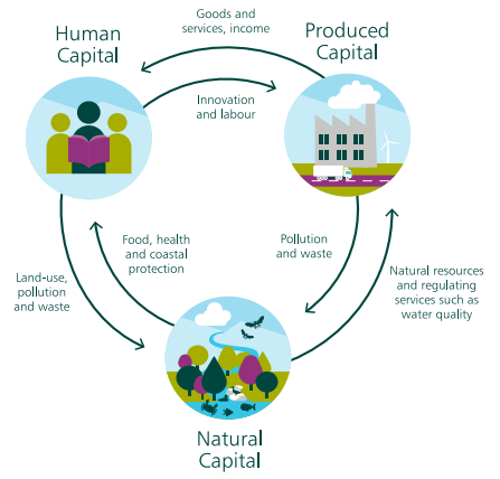

Therefore, there is a need to make the case for NbS and its co-benefits. Joanna said in Canada, authorities are realising that ecosystem goods and services can be valued and bucketed into provisioning, regulation and support and cultural aspects. They are starting to take a broader view of what is infrastructure: it is being called resilient natural and built infrastructure. These NbS co-benefits support the economy as well (see figure).  The national adaptation strategy focuses on resilient natural and build infrastructure. In the 2021 Budget, it has provisioned the Natural Infrastructure Fund of Can$200 million over three years, starting 2021-22.

The national adaptation strategy focuses on resilient natural and build infrastructure. In the 2021 Budget, it has provisioned the Natural Infrastructure Fund of Can$200 million over three years, starting 2021-22.

Joanna said coastal adaptation is not a choice between grey and natural infrastructure. Grey infrastructure may be needed to enable NbS where natural processes have already been heavily modified and NbS can enhance grey infrastructure.

To make the case for NbS, the physical, biological and social outcomes need to be quantified. Aspects to consider are water quality, aesthetics, carbon sequestration and storage, recreation and biodiversity and habitats.

Several municipalities have started inventorying and valuing natural infrastructure. National standards are being developed to prepare a natural asset inventory. Companies are interested in reflecting these values in their financial statements.

Case studies

Canada: Enormous benefits

Percé, a town in the Gulf St Lawrence, Canada, has been experiencing serious climate change impacts, due to sea-level rise, milder winters, loss of ice cover on the Gulf and changing storm patterns. In particular, the waterfront boardwalk and the building behind it have been subject to repeated damage for several years. It is becoming urgent to implement appropriate measures to protect the coast, notably to maintain tourism traffic.

Four segments of the coast were studied, defined according to their physical characteristics and land use, in addition to the anticipated risks. The cost-benefit analysis considered various options, as well as not intervening. Beach nourishment, an NbS, was the most beneficial over 50 years. The cost-benefit ratio turned out to be 68:1, with large benefits for tourism in terms of a gain in tourism revenues, fish spawning grounds, and improvements in the recreational value of the coast, quality of life and landscape.

The Netherlands: Silt to Wealth

The objective of the Program ED2050 is to improve the ecological situation of the Eems-Dollard estuary by ensuring the health of the estuary that meets the European objectives of the Water Framework Directive and Natura 2000. In Groningen, a province in the northern Netherlands, a large area of the estuary is susceptible to soil subsidence due to peat oxidation and extraction of gas and salt, and the water is highly turbid, said Albert Vos. The project turned the silt into a resource. Dredged sediment has been used to raise the level of agricultural land, reduce turbidity, and restore natural dynamics and the habitat of the coastal zone. The sediment has also been used to reinforce dykes. The farmers are enthusiastic about the opportunities this NbS approach has given them and see the advantage of using the sediment to raise their farmlands so they can continue agriculture. We combine local liveability with the quality of the area. The project works closely with local communities and the government to create a healthy climate-adaptive coastal zone economically and ecologically. The project shows how NbS can help reuse a resource that has no intrinsic value to safeguard assets.

Tackling Copenhagen’s flooding problem

Copenhagen has attempted to combine natural cost benefits with flood protection in an environmentally and socially acceptable way, said Ole Fryd. There are three examples from different parts of the city, where this has been attempted since 1980. Each presents a different approach to coastal adaptation. Two use NbS. The Koge Bay Beach park was a Nordic welfare state flagship project set up as a national project as a partnership between regional governments and municipalities. It has an independent budget, secretariat and technical staff. The Dragor Living Shoreline has seen a succession of NbS projects over time, using the principle that more is more. There have been high levels of community engagement. The third example is Lynetteholm, an artificial island off the coast of Copenhagen that will house 35,000 people and protect the city's harbour from rising water.

Typhavelles to regenerate dunes in Senegal

Presenting the example installation of typhavelles in the marine protected area of Saint Louis, Senegal, Didier Kabo and Moussa Sall said these have been built over a length of 1.5 km to help stabilise coastal dunes. Typhavelles are fences of Typha australis, an invasive aquatic plant, built to catch the aeolian sand and rebuild dunes.

In time, typhavelles form embryonic dunes, increase the length of the beach and encourage vegetation such as mangroves. They help preserve biodiversity, encourage eco-tourism and promote sustainable gardening activities among the population. This NbS approach has resulted in the return of avifauna and the regeneration of mangroves.

Communities have been trained on soft protection solutions. The site was divided into management units. Local micro-enterprises were engaged to produce the palisades of Typha australis, an invasive aquatic plant in the Senegal River and freshwater bodies. Market gardening of the plant was also developed. Thus, the project helped generate local jobs.

UK: Transformational change now?

In the UK, shoreline management planning has been based on cells each with its approach of advance, manage, to no active intervention, said Paul Sayers. The weights that different priorities are given depend on environmental improvement and benefits related to amenities, access and nature. Realignment has been successful in sparsely populated places but has faced challenges with established communities. It will take many years to move from ‘hold the line’ to ‘realign’. This shows how difficult it has been to balance the benefits of NbS with the economy. Having said that, it is possible to make the case for NbS on a case-to-case basis. To decide the strategy to use now, it is critical to visualise what the future might look like. Communities need to be supported to take and implement decisions. The UK has always incorporated coastal adaptation activities with a public funding perspective.

Floating development Vs land reclamation

Most coastal cities were going for land reclamation which was harmful to ecosystems. Reclamation is not as adaptive as floating communities or development, said Lin Fen-Yu (Vicky). While there are no perfect solutions, we should experiment with good practices to manage increasing risks. It is important to have evidence for making policies.

Funding for coastal adaptation

Each example has used funding from different sources, the main one being public funding from the government and communities. In the UK, coastal adaptation has been partly publicly funded and partly by the communities and local governments. Denmark considers co-financing so public financing is for the common good, with the understanding that the intangible value NbS provides seem to harness these better than conventional infrastructure. The community and municipalities share part of the costs. In The Netherlands, the Eems-Dollard project is also publicly funded. In Canada, 40 local government have valued their natural resources and want to put them on their financial statements. This ecosystem accounting will give natural assets their accounting head. In Calvary, for example, natural assets were the fourth most valuable assets.

Governance and policy to support NbS

The key to good legislation to enable NbS for coastal protection is good evidence that it works, said Floris Boogard. These should emphasise the ecosystem services and other benefits of NbS. Further research is needed on the cost-benefits of NbS to overcome doubts about implementing NbS. Even the diverse case studies presented by the speaker did not reflect the multi-disciplinary aspects. There were no perfect solutions, underlining the need to experiment with good practices to manage increasing risks.

NbS, the new normal

NbS is the new normal and innovative solution, summarised Joanna. Some countries had advanced in adopting NbS for coastal erosion, but it was clear that it needed to be highly localised; one size would not fit all. NbS needed to be beneficial to local economies and communities, take into account local conditions and build on and along with grey infrastructure. NbS could leverage benefits from the circular economy and provide innovative ways to work with natural processes. Not all innovation had to do with technology but involved working with natural physical processes.

Further resources

-

The presentations made at the webinar

The presentations made at the webinar

-

Coastal protection examples from Denmark

Ole Fryd describes how Denmark is implementing the NbS agenda to protect, accommodate, retreat, or avoid.

combining_natural_and_grey_infrastructure_in_denmark.pdf

combining_natural_and_grey_infrastructure_in_denmark.pdf

-

Eems Dollard 2050 and COREPLAT

Albert Vos on how a climate adaptive coastal zone is being developed in the Netherlands by implementing restoration projects

ems_dollard_core-plat.pdf

ems_dollard_core-plat.pdf

-

Strategy takes time

Paul Sayers argues that it take to implement a transformational change at the coasts.

time_for_a_transformational_change_at_the_coast_in_uk.pdf

time_for_a_transformational_change_at_the_coast_in_uk.pdf

-

Upscaling and replicability to other areas

Floris Boogard describes how to work towards an climate adaptive coastal zone by implementing restoration projects.

upscaling_and_replicability_to_other_areas_in_the_netherlands.pdf

upscaling_and_replicability_to_other_areas_in_the_netherlands.pdf

-

Marine Protected Area of Saint-Louis, Senegal

Didier Kabo talks about the feedback from experiences on the installation of typhavelles.

didier_kabo.pdf

didier_kabo.pdf

-

Creating new space on the water

Lin Fen-Yu describes how floating spaces create land for agriculture without competing for scarce land.

lin.pdf

lin.pdf

-

Three more examples of floating development

Floating houses to fight climate change in Holland. Rising sea levels caused by climate change are threatening coastal areas worldwide, a recent IPCC report shows. Low-lying Netherlands is already getting prepared by building floating homes and redirecting rivers. [Full article]

Are floating homes a solution to UK floods? Recent flooding across the UK has seen hundreds of householders desperately trying to prevent water from entering their houses. But what if your house was buoyant - rising at the same level as the surrounding water? [Full article]

Maldives floating city. This is the first development of a new era in which Maldivians return to the water with resilient eco-friendly floating projects. [Full article]

Trending Discussions

From around the site...

“Absolutely interested! I'll connect via email to discuss reviewing and enhancing the Economic Analysis of Climate...”

Adaptation-related events at COP28 (all available to follow/stream online)

“Please check out these adaptation-related events taking place at COP28 - all available online (some in person too if...”

Shining a light for biodiversity – four perspectives to the life that sustains us. Four hybrid sessions.

“30 November to 19 December 2023 - Four Sessions Introduction The SDC Cluster Green is happy to invite you to the...”