Summary

Prolonged droughts in the western United States have exacerbated the threat of forest wildfires. In 2021, the Dixie fire, the single largest in California’s history, burnt 1 million acres and cost $610 million to suppress. This has prompted forest supervisors to prioritise responses. But financing resilience at the scale needed is beyond the ability of any single agency, government or private. It is estimated that US$ 60 billion is needed to protect all the 50 million acres of forests at risk of fire in the US.

Enter Forest Resilience Bonds (FRBs). This public-partnership model is part of the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) efforts to bring new resources to forest management. It is gaining ground rapidly.

FRBs scale up rapidly

In 2018, the Yuba Project pilot in the Tahoe National Forest raised $4 million to protect 15,000 acres of forests and enhance water security of the Yuba River Watershed. Three years later, the second FRB called Yuba II raised four times as much, $25 million, to protect 48,000 acres. FRBs aid in improving watersheds, as soot and burnt wood from wildfires can contaminate local water resources and impact water treatment works.

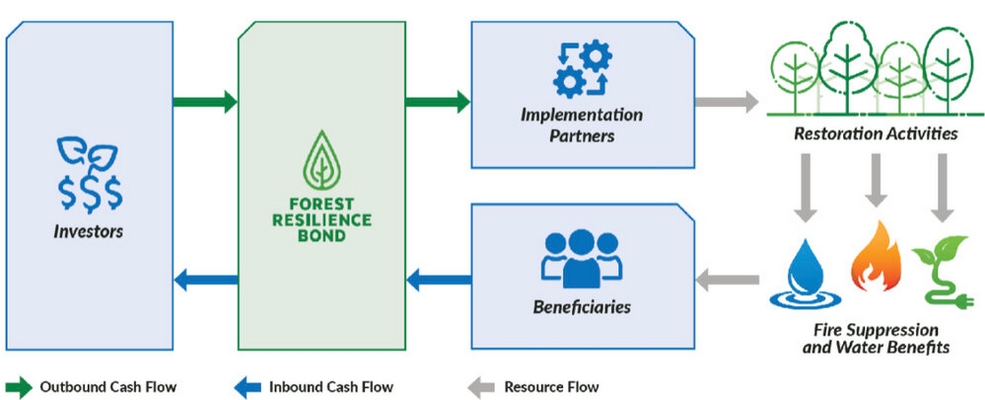

FRBs leverage finance from private and philanthropic investors to fund forest restoration and improve water security. The investors are paid back by the beneficiaries which include local utilities and the government, in this case, the State of California and the Yuba Water Authority (YWA), at contracted rates. The Tahoe National Forest (TNF) provided in-kind support for project planning, development, and execution.

Meryl Harrell, USDA Deputy Under Secretary for Natural Resources and Environment said in a press release, "Public-private partnership models, like the FRB, that leverage private investment for public good are integral to the paradigm shift needed to address the risk of catastrophic wildfires. Yuba II demonstrates that the FRB can be scaled to support the Forest Service’s goal to treat 20 million acres over the next decade to mitigate the risk of wildfire."

Leveraging multiple sources

This kind of corporate support for financing models to leverage utility and state funding was the main goal of a grant from the USFS Innovative Finance for National Forests program to a consortium, including World Resources Institute (WRI), Bonneville Environmental Foundation (BEF), American Water Works Association (AWWA), and Blue Forest Conservation (BFC). Silk, a plant-based food and beverage company owned by Danone, is funding Yuba II through a partnership with BEF.

In 2018, BFC initiated the Yuba Pilot Project in partnership with WRI and Encourage Capital. BFC was the investment developer and project sponsor and brought together the US Forest Service (USFS, the landowner), the National Forest Foundation (NFF) as the implementer, the State of California, and the Yuba Water Authority (beneficiaries and payers), and investors for both the pilot and second phases. An FRB Yuba Project LLC was set up as a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) that served as the debt issuer. It mitigated the financial risks of all parties to the project to the greatest extent possible.

The investors in the pilot were the Rockefeller Foundation, Gordon & Betty Moore Foundation, Calvert Impact Capital and CSAA Insurance. In 2021, the Yuba II FRB was launched by WRI, BFC, NFF, USFS, YWA, and the North Yuba Forest Partnership (NYFP). CSAA is the lead investor in Yuba II as well. The other investors are Hall Capital, ImpactAssets and RSF Social Finance.

A partnership

The activities included forest restoration, enhanced water security, and protected nearby communities and will be scaled up in the second phase. The pilot allowed the Tahoe National Forest (TNF) to complete projects in four years against the projected 10-12 years. Yuba II is supported by the North Yuba Forest Partnership (NYFP) that is a diverse group of nine organizations. The TNF is providing in-kind support and services and the resources for planning and permitting the project. NFF is the project's primary implementation partner, leading much of the forest restoration work on the ground.

The two beneficiaries—YWA and the State of California—reimbursed the investors. For the pilot YWA committed $1.5 million, and the State provided $2.6 million. For the FRB II, YWA has committed $6 million. The Moore Foundation has committed $2 million and Inherent Foundation, $1 million, in Program Related Investment.

FRBs support a greater social good, such as reducing deforestation, maintaining water quality, promoting biodiversity, and sequestering atmospheric carbon.[1] They make finance available upfront from investors, who recoup their investments from beneficiaries such as water or power utilities, municipalities, private companies and communities. For example, the Tahoe National Forest forms part of the watershed that supplied Yuba County. Were a fire to start in the forests, woody debris and soot and sediments would enter reservoirs, clogging hydroelectric plants and driving up costs for water and electrical utilities.

Meeting a need

Todd Gartner, WRI’s Cities4Forests Director, said, “The USFS does not have the budget to treat the 50 million acres of forests at high risk. This effort leverages federal resources to scale restoration and reduce risk bigger, better, and much faster by enabling collective action amongst federal and state agencies, utilities, and corporations. The USFS is responsible for long term stewardship. Maintenance treatments will be needed 15 years down the road. We are currently exploring financing approaches to cover these costs.”

Despite the name, FRBs are neither a bond nor a registered financial instrument. They are a partnership or more specifically a project contract, structured as a loan supported by contracts, where two or more parties agree on “pay-for-performance” or “pay-for-success” terms. Typically, a public entity or the government agrees to pay a return to private investors only if the implemented program meets or exceeds previously agreed upon environmental impact or performance targets. Thus, part of a project’s risk is transferred from the payer to private investors[2].

This article has benefited from valuable inputs from Todd Gartner at WRI and Zach Knight at Blue Forest Conservation

[1] Chung-Hong Fu, Bonds for Trees: A Good Idea Hoping to Become Real, Journal of Environmental Investing 3, No. 1 (2012). Accessed from https://www.tireurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Review-of-Forest-Bonds-The-Journal-of-Environmental-Investing-TIRs-Chung-Hong-Fu-05-24-12.pdf on 20 June 2022

Further resources

- How the Forest Resilience Bond Works

- New FRB will Finance $25 Million of Restoration to Reduce Wildfire Risk on the Tahoe National

- Investors Think They Can Make Money Reducing Wildfire Risk

- The Forest Resilience Bond: Leveraging Innovative Finance, Science, and Partnerships to Fight Drought and Wildfire

Trending Discussions

From around the site...

“Absolutely interested! I'll connect via email to discuss reviewing and enhancing the Economic Analysis of Climate...”

Adaptation-related events at COP28 (all available to follow/stream online)

“Please check out these adaptation-related events taking place at COP28 - all available online (some in person too if...”

Shining a light for biodiversity – four perspectives to the life that sustains us. Four hybrid sessions.

“30 November to 19 December 2023 - Four Sessions Introduction The SDC Cluster Green is happy to invite you to the...”